Michelle Huang Commissioned Painting Series: 1528 – 1698

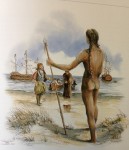

A few months back I commissioned the talented Michelle Huang to paint a portrait of two Karankawa Native Americans: one male, one female. Often being caricatured, this painting of the Karankawas served as a more accurate depiction of the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Karankawas. In creating the piece, Michelle used first-hand descriptions from those eras, photography on this website for the portrait’s environment, and live models. I purposefully avoided providing her with other artists’ interpretations of the Karankawas (Tapia’s among others) and more telling quotes from different time periods for fear that it would influence the painting.

You can see the sources Michelle worked with below. These first-hand descriptions of the Karankawa make up almost every account of these coast people in a nearly two hundred year span. They come from primarily three sources: Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, who in 1528 crash-landed on what was likely Follets Island among the Capoque (a Karankawa-cultured tribe); Henri Joutel, a trusted captain of Sieur de La Salle’s ill-fated mission to locate the Mississippi; and Jean-Baptiste Talon, who as a boy was abducted from Fort St. Louis by the Clamcoeh. More Europeans encountered and wrote about the Karankawa during this time period, but few provided further information on what they looked like.

I am awe-struck by the phenomenal work Michelle has done. To see more of her work or to purchase a few prints, you can check out her website here.

Depictions other artists have made of 16th & 17th century Karankawa Indians:

FIRST-HAND ACCOUNTS KARANKAWA APPEARANCE 1528-1698

1528 |

Alvar Nunez Cabeza De Vaca’s Account |

“The people we encountered there are tall and well formed”

“They have no other weapons than bow and arrows which they are most dexterous.

Their bows were said to be of similar height as them, so in the five foot plus range (see Austin, Smithwick, Jenkins). Their arrows were recorded as being three feet long, made out of reeds, and had three feathers that the Karankawa attached to the end. The arrow points were made out of “sharp stone, fish bones, or fish teeth.” Although Cabeza de Vaca said that their only weapon was the bow and arrow, the Karankawa also made use of daggers made out of sharp rock or shell, clubs, and lances.

“The men pierce one of their nipples from side to side, and some both of them; through this hole they thrust a reed as long as 2 and ½ spans (~18 inch) and as thick as two fingers.

“They also perforate their lower lip and insert a piece of cane in it as thin as half a finger.

“They used red ocher with which they rub and dye their faces and hair.”

Red ocher was typically only obtainable through trade with Indians from the mainland. It is likely that it was considered a luxury item and would only be worn or put to use during funerals or other significant ceremonies.

“They are so badly bitten by mosquitoes that it seems as if they had the disease of Saint Lazarus (leprosy).”

“[The wear] tassels made of the hair of deer, which they dye red.”

It can be assumed that they might have worn these tassels in their hair.

1685 |

Henri Joutel’s Account |

“The men were all naked; several had deer skins that they slung across their backs as gypsies do.”

This skin that slung across their back would be cloak-like and made of buffalo or deer hide. When this encounter occurred it was during the winter and conditions were much colder than they are now (Little Ice Age). During the summer months, this cloak would not be worn and would be used likely as a blanket at night or as a covering on their huts.

“As they had no way to fasten the items on themselves which La Salle had given them [implying nakedness; no loincloths], we attached the gifts to their arms and neck [implying that they had bracelets and necklaces].

“We saw several women who were naked except for a skin that encircles them and covered them to the knees.”

The skirt was also probably made from buffalo or deer skin.

“They had some markings on their faces and therefore were not very pretty.”

These tattoos are a commonality in almost all descriptions of the Karankawa; however I have found little to no information in this time period on how these tattoos looked.

1687 |

Enriquez Barroto Account |

“They went naked and with their bows and arrows.”

“He persuaded two or three of the Indians and regaled them with [wheat] that they should come aboard. Seeing that they did not wish to, he ordered Juan Poule to take hold of one and make him do so, and the ensign and another together, but the three could not subdue him [the Karankawa], because all these Indians are of great stature and very robust of limb.

1698 |

Talon Brothers Account |

“All these nations have the custom of going every morning at daybreak to throw themselves into the nearest river, almost never neglecting to do so, no matter what season, even when the water is frozen. In this case, they often make a hole in the ice and dive into it….then they wrap themselves in buffalo hides rubbed soft like chamois leather, which they use as robes, after which they walk about for some time.”

This daily bathing ritual probably meant that the Karankawa were not nearly as dirty as some Europeans later suggested. It’s also important to note the cold weather clothing employed by the Karankawa — the buffalo hide robe/blanket.

“They all went naked like them and every morning at daybreak, in any season, they went to plunge into the nearest river.”

“[The Karankawa] first tattooed them on the face, the hands, the arms, and in several other places on their bodies as they do on themselves, with several bizarre black marks, which they make with charcoal of walnut wood, crushed and soaked in water.

In this instance, the Karankawa had spared and adopted a number of children from a French fort they had ravaged. Because it is apparent the Karankawa adopted these children, the tattoos given to the children were likely the same they gave to their own. These tattoos covered the entire body, and every member of the band wore them. The “bizarre black marks” were significant enough that as one historian mentions, “[they] provoked curious stares from Europeans seeing them for the first time.” Other historians have ventured to say, I think rightly so, that the tattoos were a means of conveying status, marital availability, and could act as a passport through the country-side.

“The Clamcoehs [Karankawa] wear mourning for their dead parents by smearing their body with a black substance made with charcoal of walnut wood soaked in water.”

“One sees among these peoples only males [that are] well built and well formed, as well as those of the other sex, because, if it happens that a woman gives birth to a deformed child, she buries it alive as soon as it is born.”

“All the savages, generally; are strong and robust and made for all sorts of hardship.

On Hair and Tattoos

In the sources ranging from this time period I have not come across any that mention of how the Karankawa wore their hair. As this is the case, I will give you a bit of information that later authors wrote. They say the Karankawas black hair was worn long, as far down as to their waist and that they cut the front so it did not obscure their vision. The men would also braid trinkets in their hair.

“His face has tattoos….with a black line that goes down the front to the end of his nose and another from the lower lip to the end of the chin, another small one next to each eye and, on each cheek a small black spot. Like the nose, the lips also are blackened, and the arms are painted with other markings.

I have not been able to find a detailed account of the Karankawas tattoos in this time period. This source isn’t speaking about the Karankawa. It is about their neighbors, the Akokisa, but it should give you an idea of what these tattoos typically looked like.

“One, two, or three black lines are tattooed on their faces, beginning on the forehead and running across the nostrils down to the chin. The women’s breasts are painted with numerous concentric circles around the nipples.”

Again, this is not describing a Karankawa. In regards to the Karankawas tattoos I think you’re going to have to take some artistic liberty.

The Karankawa are a conglomerate of smaller bands and clans. Akokisa were apart of this collective.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are right in that the Karankawa were made up of many different bands and clans. The term “Karankawa” is an all encompassing label for these groupings of people. They all shared a similar culture and spoke the same language (albeit with different dialects). The Akokisa, however, were not of the Karankawa culture, instead they were more closely related to that of the Atakapa culture.

The first European encounter of the Akokisa comes from Cabeza de Vaca’s famous Relacíon. In it, they are referred to as “the Han.” They co-inhabited what was likely Follets Island with another group Cabeza De Vaca calls the Capoque, which were a people from the Karankawa culture. The Han and Capoque lived together on Follets Island, but despite sharing a similar lifestyle, they spoke different languages and had different cultural practices.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Akokisa, you should definitely check out Henri Folmer’s english translation of François Simars de Bellisle’s account of life among them after being shipwrecked on Galveston Bay in 1719. You can find it here: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30240565?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents.

If you are not able to access that then I can hook you up, just tell me — it really is quite the read! Thanks for the comment, and if you have any more questions or observations, please send them my way!

LikeLike

Additionally, Lawrence E. Aten does a wonderful job of briefly defining coastal ethnic groups in his Indians of the Upper Texas Coast (see pages 28-41).

His book isn’t widely available, so I may have to post that section on the website if you’re interested.

LikeLike

Of further interest, some historians have posed doubts that the Capoque, who are later associated with the Coco, should even be considered as a Karankawan group considering many of our accounts of these people and where they inhabited does not closely match where the other bands of Karankawa lived. To learn more, see Foster’s Spanish Expeditions into Texas — especially the sections in which he talks about missions not considering the Coco as a Karankawa cultured tribe.

LikeLike

M’tchawa. Nayi Tza-keej n’ah t’uh. Muda Awa? How are you? I am looking for my relatives. Where are you?

N’ah Tu’h, my relatives, if you are out there, reach out. 713-562-1398. Your relatives are in Houston, Galveston, Dallas, Alamo, Donna, Corpus and even as far west as california. For many centuries we have been in hidding. We are hidding no longer. Members who have survived from different clans are still here. We are very small in number but we are here. You have a language. You have relatives. You are not alone. You are no longer the only one. We no longer have to live in secret. Our lives are no longer in danger as long as we have each other.

-FlyingBear Two Winds, Karankawa Kadla, Uchi Kissa (Karankawa, Coyote Clan)

LikeLike

M’tchawa? Nayi Tza-keej n’ah t’uh. Muda Awa?

How are you? I am looking for my relatives. Where are you?

Karankawa Kadla, please search for us on the internet, on Facebook, on Instagram.

Call yourself now by our true name, the Karankawa Kadla and revive our ancestors culture, language, spirituality, and traditions with us.

We are still here, we are not extinct, we are coming together.

I love you, I miss you.

LikeLike